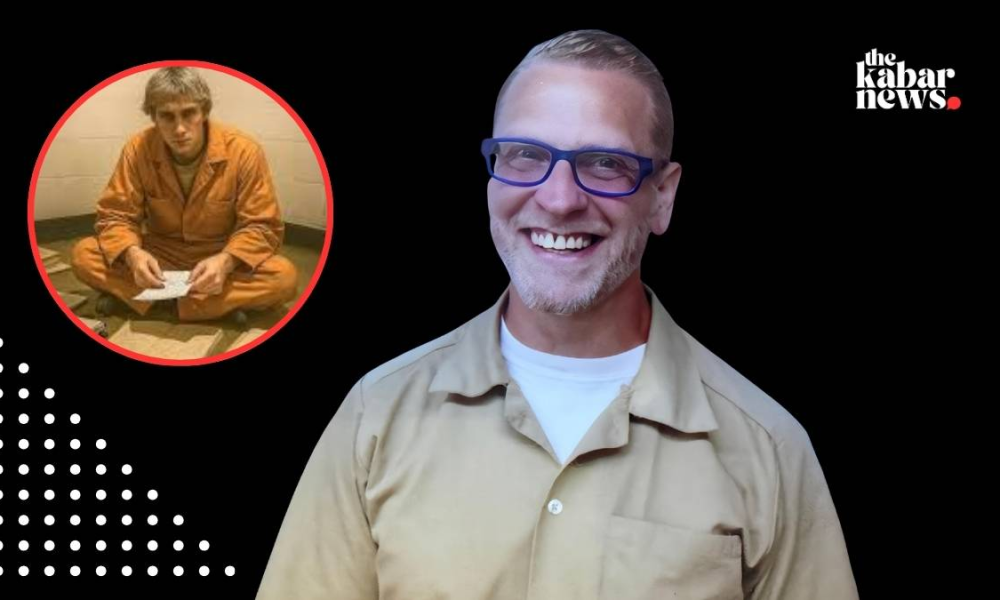

When a math textbook changed his 25-year murder sentence

Thekabarnews.com—Christopher Havens entered a Washington maximum-security prison with a life of drugs, violence, and crime. His prospects seemed grim at thirty-one in 2011. Most people lose hope and...

Thekabarnews.com—Christopher Havens entered a Washington maximum-security prison with a life of drugs, violence, and crime. His prospects seemed grim at thirty-one in 2011. Most people lose hope and ambition in prison. Christopher gained time in prison for the first time.

Cellmates left a math textbook for Christopher. Christopher picked it up out of boredom rather than genuine interest. Math was never his forte. He dropped out without direction after scraping through school. But alone in his cell, with long hours and no distractions, he worked through the issues.

Table Of Content

It was unexpected

The logic worked. The rules held. Math gave answers that were right or wrong and rewarded patience and precision in a chaotic world. There was clarity where everything else failed.

He requested more jail education books. Harder ones follow. Self-taught algebra. Then calculus. Then there are complex topics most students never face outside of college. He filled pages with symbols and proofs alone at night.

He reached boundaries. Concepts were too complex to understand alone. He needed advice.

Christopher dared to write to professional mathematicians worldwide for help.

Many never replied. Quite understandably. Convicted murderers writing about abstract mathematics rarely reach academic inboxes. However, University of Turin mathematician Umberto Cerruti responded.

Cerruti was noncondescending, and challenged Chris

He delivered number theory, one of mathematics’ most abstract and difficult disciplines, and gave questions that would challenge even trained researchers. Christopher wrote pages of meticulous, original handwriting.

In a prison cell, Christopher explored continuous fractions and quadratic irrationals, which Euclid studied over two millennia ago, using just paper, pencils, and books. It was not homework. It was research. Everyone was astonished by the next moment.

Christopher created something unique

He discovered new number theory relationships that others had missed. Cerruti collaborated. They checked. It is verified. It endured.

This achievement is not particularly remarkable for someone who is incarcerated. Yes, that was impressive.

A reputable peer-reviewed journal, Findings in Number Theory, published Christopher Havens’ findings in 2020. A man in prison for decades without a college degree, computers, or university libraries contributed doctoral-level mathematics to human understanding.

The intellectual world noticed. The mathematician shared the paper. Teachers used his experience to demonstrate that opportunity, not background, determines potential.

Journalists and filmmakers followed. Prison-education supporters said the example showed that learning can change lives in the worst conditions.

The violent prisoner found discipline, purpose, and a way to give back. Christopher co-founded the Prison Mathematics Project, teaching jailed kids worldwide to study math and believe in futures bigger than their worst sins.

He studies problems that pose challenges to professional mathematicians. He cannot be released until 2036. His freedom to think, create, and contribute is already there.

Christopher Havens’ narrative does not negate criminality. It indicates that humans are more than their worst deeds. Such creativity does not need privilege. Education can unlock society’s rejected minds.

An antique math textbook left by a cellmate opened a mind that could solve two-thousand-year-old problems. That should alter our views on punishment, education, and potential. Someone in a prison cell is tonight staring at a page of numbers, unsure of their future.

No Comment! Be the first one.